"Shotgun Summer" Published by Dirtbag Magazine

My dad wasn’t a hunter. He was raised in the city and abhorred guns. As a teenager, he witnessed his best friend’s father kill himself with a 12-gauge shotgun. He saw the whole catastrophe, a final wave; the violent jerk of a trigger. Dad rarely talked about that tragedy. We just knew not to bring up the topic of guns around him. You could see the fear, the panic, and the pain in his eyes when a scene on TV reminded him of that day.

After my parents’ divorce, Dad wasn’t around much. I grew up really only seeing him every other weekend. My father did his best to instill a love for the outdoors in his children. He made sure to share his passion for fishing with my siblings and I. I owe a debt of gratitude for those bug-spray choked summer days spent catching catfish and bluegills at the Greensboro, NC Jaycee Park. That’s where my dad’s outdoor prowess seemed to end. I’d have to learn what I considered “manly” things from others. Things like how to properly shoot a weapon.

My friend Nathan’s dad, Bill, had all sorts of guns and animal heads on the walls of his home. He was a jack of all trades, a handyman by profession, and the definition of an outdoorsman. I was enamored that he not only knew how to hunt and fish, but also how to prepare wild game to eat, mount deer skulls, and handle a multitude of guns. Blood-stained mossy oak camouflage was his uniform of choice. Bill not only hunted for sport, but also to provide meat for the table. It wasn’t uncommon for him to have venison in the crockpot, squirrel stew on the stove, or in the case of this afternoon, bullfrog legs in the skillet.

My brother Shawn, Nathan, and I finished our fried frog legs and prepared to head back into the wild unknown, when Bill stopped us at the door. He told us to be back at 3:00 pm. This was in the days prior to cell phones. Knowing we’d be too far for him to yell; he would shoot a shotgun to signal our return. A few hours went by, and as brothers tend to do, Shawn and I began to fight. As we wrestled on the ground, Nathan jumped in with my brother. They both took turns beating me up. I wiped tears and mud from my eyes and shouted, “the heck with you guys I’m going back to the house.”

As I approached, Bill looked up from the hood of his two-toned F-150 and then at his watch. He asked where the other boys were, since it was about time for us to get back anyway. I explained that we got into a fight and I walked back alone. To ease my mind on the beating I’d just taken, Bill asked if I’d ever shot a gun before. I lied. The truth was, the only guns I’d ever shot were of the BB variety.

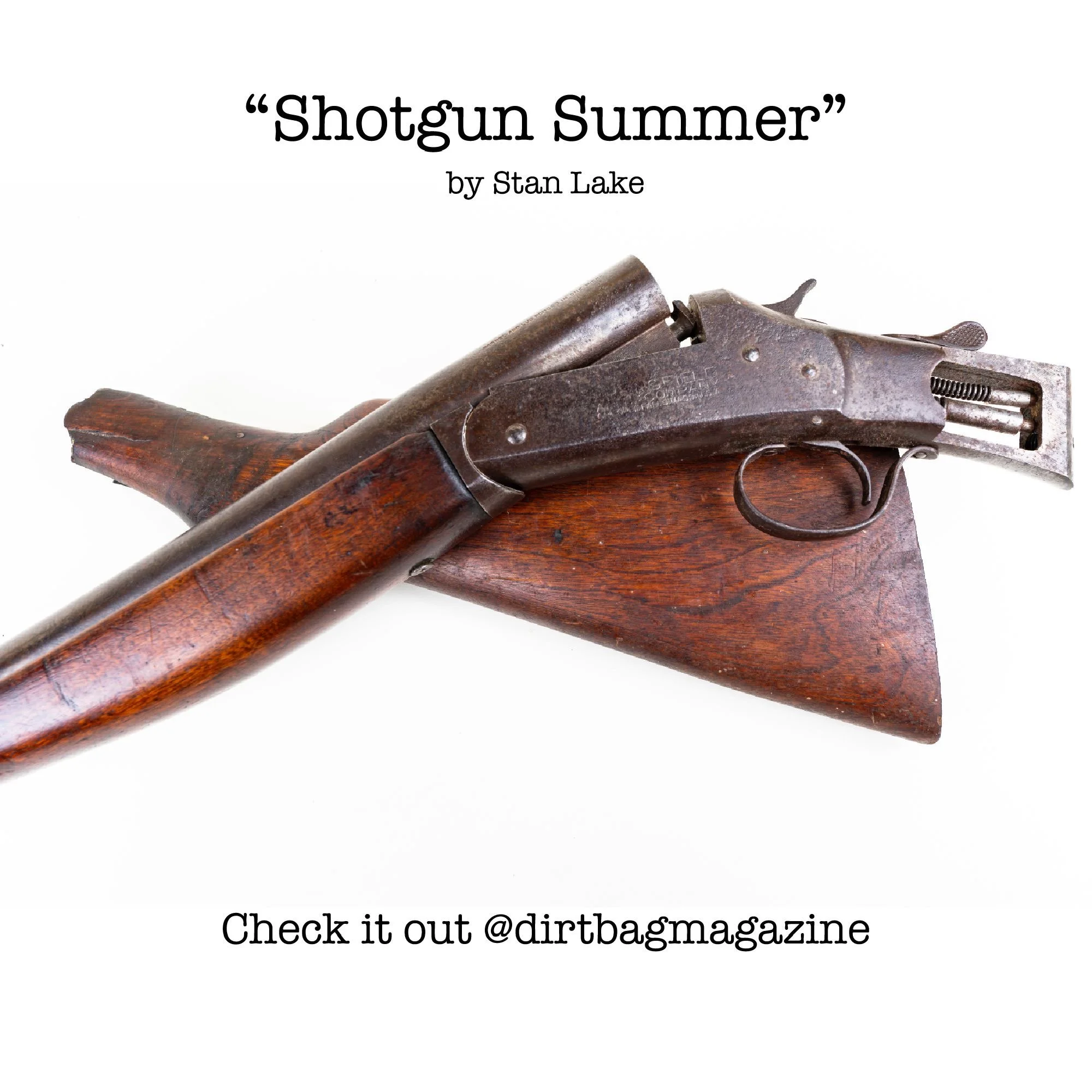

He reached into the pickup and pulled a 12-gauge shotgun from the rack on the back glass. It was one of those break barrel shotguns that only held one shell. Bill pulled the hammer back and handed me the gun. It was almost as long as I was tall and heavier than I expected. I almost immediately regretted lying about my aptitude with firearms. I had no idea what I was doing. I figured as long as I had control of the weapon and stayed away from the business end, I would be alright.

Bill offered little direction, taking me at my word, as men are supposed to, that I knew what to do. “Hold it tight. Squeeze the trigger.” Trembling, I felt like I was breaking unspoken rules laid out by my father. I held the shotgun about a foot away from my shoulder, in hopes of avoiding getting a nasty bruise. As soon as Bill turned his head, I pushed the shotgun out until the bend in my elbows straightened. I yanked the trigger.

The gunshot was louder than I imagined. Everything went white for a second. My whole world was ringing and tingling. Black dots appeared as the shotgun flipped and spun in slow motion, as if suspended in the air in front of me. Horrified, Bill turned back to look at me and saw what I had yet to realize.

Blood dripped from my face like a leaky garden faucet. In my shock, I did not register the blood splattered in the piedmont dust was mine. I had no idea of the extent of my injury. The shotgun rested on the ground in front of me, as if I had lied to it too.

Bill ran up and wheeled me around by the shoulders. The look on his face would have brought terror to any rational person. He grabbed a washcloth, then my jawline. In a high-pitched panic, he screamed, “hold this on your jaw. Tight. Whatever you do, don’t look in the mirror. We have to call your mom.”

Almost immediately, I disobeyed his order. In the bathroom, with temptation in front of me, I removed the washcloth and looked in the mirror. That was a mistake. The terror sunk in.

My jawline was flayed open like a hatchet wound. I could nearly see the bone. The jagged curved gash was half an inch wide and close to two inches long. I could put my whole thumb into the ripped flesh. I don’t remember feeling much pain, just a prickly numbness. My concern immediately shifted to facing my mother. A fate more worrisome than the prospect of a catastrophic injury.

With trepidation in his voice, Bill called my mom as he threw me into the cab of his truck. We raced down the dirt road towards town, kicking up dust and throwing chunks of slate gravel. Upon hitting the paved road, I bounced hard enough in my seat to hit my head against the window. My hands still clasped the blood-soaked rag against my jawline. Bill was feverishly apologizing and lamenting the fact that my mother was going to kill him. He seemed worried about me, maybe more so about what my mother would do to him.

With a smoldering rage, my mom stood outside our minivan at the half-way point where they agreed to meet. She didn’t have the time or energy to be angry with Bill, yet. She just asked, “What made you think it was okay to let my son shoot a gun?” My mom moved the washcloth and without changing her facial expression said, “OK, get in the van. We are going to the hospital.” She stayed calm, like moms are supposed to. Raising three kids on her own, she was strong like that. She had to be.

One look at my face rattled the pediatrician. He clearly didn’t see injuries of this magnitude normally and promptly referred us to a plastic surgeon, but as it turned out, they were all out of town. Our only option was an ear, nose, and throat doctor by the name of Dr. Duck, supposedly the only person qualified to suture a wound that complex. My mother tried to break the tension with humor, “Great, so you mean we’re going to have a quack sew you back up.” We both giggled nervously as she screeched into the parking lot.

With what felt like four bee stings all at once, Dr. Duck injected me with Lidocaine. That was the first time I felt any pain. I assumed they would knock me out to do the procedure, but I was wrong. I was awake for the entire four-hour surgery. The gravity of the situation sunk in as I felt every tug and pull of the sutures cobbling my face back together. The laceration required fifteen stitches inside and some thirty stitches outside. When it was over, I looked in the mirror at the line of irregular black knots on my jaw and felt lucky that it hadn’t been worse.

A few days after the accident Bill was still a wreck. He destroyed the shotgun when he got back home from handing me off to my mother. I’m not sure if it was out of remorse or an effort to destroy evidence. A few days later, Bill brought me the hammer from the dismantled 12 gauge. The offending part that slashed my jawline. He thought I should have it. I put that hammer on a dog tag chain and wore it as a necklace the rest of the summer. It, along with my fresh scar, were both worn with pride.

I barely touched another gun until I was in Army Basic Training close to a decade later. I had become wary of guns, perhaps rightfully so. Just like my father before me, a gun left a physical and psychological imprint on me. The scar on my face reminds me of the lessons I learned that summer; the importance of following instructions; not lying about my personal experience. Half-cocked theories and painful realities are only separated by the jerk of a trigger.

Stan Lake is a writer, photographer, and filmmaker from Bethania, North Carolina. His work has been published in Reptiles Magazine, Wildlife in North Carolina, SOFLETE, The Tarheel Guardsman, and both Dead Reckoning Collective Poetry Anthologies. He has written 3 Children’s books currently available on Amazon. He filmed and directed a documentary about his time in Iraq called “Hammer Down.” He spends most of his free time knee deep in swamps chasing snakes and frogs with camera in hand. You can find his collected works at www.StanLakeCreates.Com